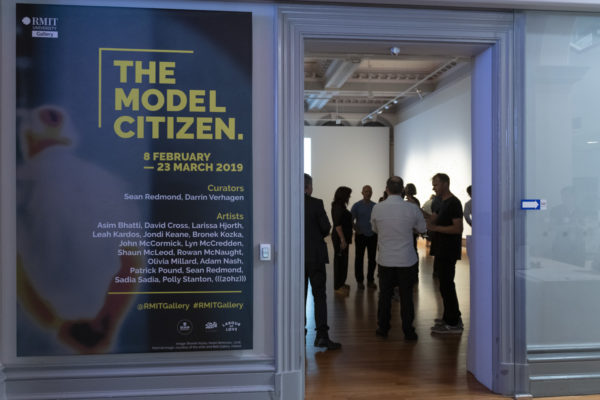

Exhibition8 Feb – 23 Mar 2019

The Model Citizen

Are you a model citizen? Meet the micro lenses of surveillance and audit culture; the algorithm of benign search engines; the political…

Sadia Sadia – In Conversation with Evelyn Tsitas

Edited transcript of the artist talk on 1 March 12:30pm, 2019 – as part of the exhibition The Model Citizen

RMIT alumnus Sadia Sadia is a Canadian-born UK-based installation artist working across a wide variety of media, including sound, still and moving images. Her creative practice-based PhD research examined the key drivers of the cathartic, epiphanic or transcendental experience within encompassing installation artworks.

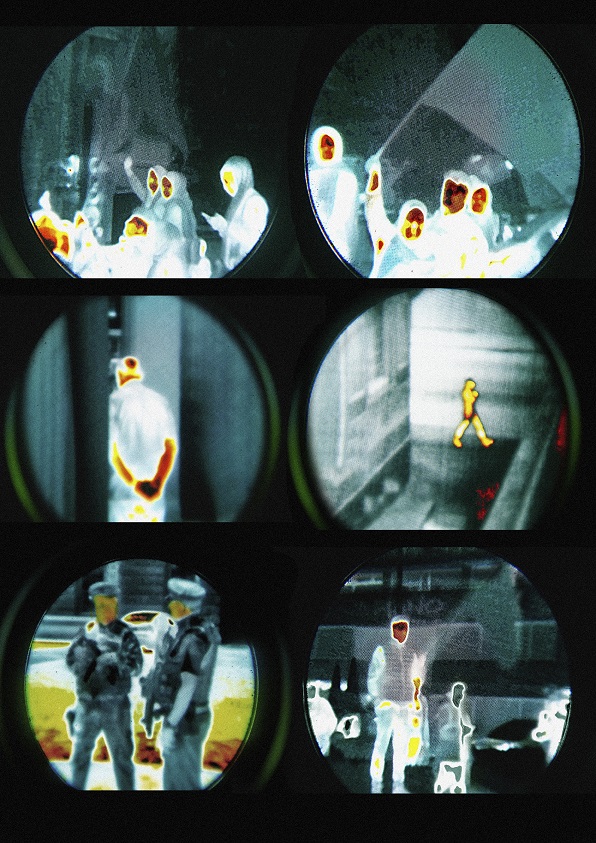

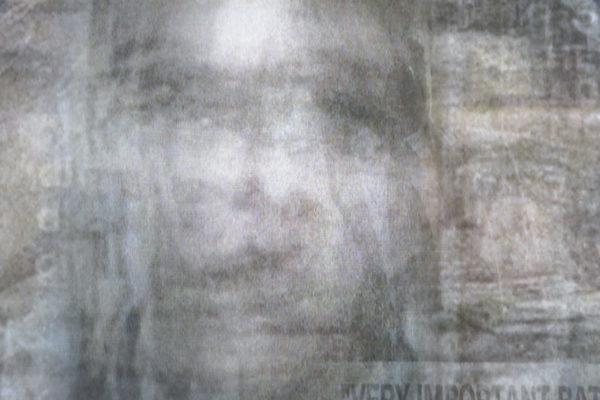

Sadia Sadia: My interest is in how people are emotionally affected by immersive film art installations comprising sound and moving images. One of the things that I’ve always wanted to do is witness the complete and proper installation of my work ‘Ghosts of Noise’. ‘Ghosts of Noise’ comprises twenty channels of male and female newsreaders, newscasters and correspondents. The central image, ‘Blend’, is in fact a non-gendered image; it comprises layered images of both men and women to create the illusion of ghosts. A ‘ghost of noise’ is ambivalent, it can be read across a whole spectrum of interpretations. I had started to internalize this level of noise and I found it really troubling because suddenly it was a phenomenon in my consciousness that was palpable.

Evelyn Tsitas: We will come to the development of this work but I would like to start at the beginning. And that beginning is your Wikipedia page and your initial career as a record producer. And from there ending up producing Ghosts of Noise, which is such a technical, complex work. Can you talk about that?

Opening night, The Model Citizen, RMIT Gallery, 2019. Photo by Margund Sallowsky.Sadia: Yes, of course. I started out as a record producer and I think that when I was signed to EMI Canada in the late 1970s I was among the first women in the world to be signed to a major label as a record producer. It’s an interesting story which I’ll tell you in brief here. I was working with a band, we went into a studio and I borrowed money to produce a record.

The album had what they called “legs out of the box” was signed by a small independent and eventually we wound up being signed by EMI Canada. The director of EMI would not sign the band without signing with the producer at the same time. Nobody at that point knew that I was female. So, when I turned up to sign the contract on the day it was something of a revelation. But my career as a record producer came about also because at the time I was speaking with an American businessman and explaining the job that I was doing in the studio and what my role was and going through the material and he said “Sadia, that’s what record producers do”. And a lightbulb came on over my head and I suppose the rest is history.

Evelyn: We’re talking about the time before people could just produce records on their own. These were the times when getting studio time was immensely expensive.

Sadia: Yes well it was a completely different world and you have to remember that these were analogue days as well where we worked with massive reels of two inch tape. So it was almost impossible to release a record without going through the gatekeeping process, which is going through an A&R department, getting signed by major label or at least by an organization that had the kind of money that it took to make an album. This is back in the days when albums cost in the tens and hundreds of thousands of pounds. So it was a completely different world, and I think the democratization of music making and production of many other art forms has served us both well and badly.

When young people come to me and say “what should I go into?” I say “Be a curator!” Since everybody now has the means of in their bedrooms, there’s an absolute tsunami of material. I used to think the gatekeepers were surplus to requirements and I’ve changed my opinion on that considerably. I think that there’s a massive untapped market for websites that specialize in nothing but curated works for people who share the tastes of the person who is making the selection. So, yes, I’d say if you want to go into anything go into curating because everybody can make an album now and everybody can produce video now and we have to start thinking about being discriminating again.

Evelyn: It’s interesting that we came to this turning point at which anyone could produce anything. So tell me about what happened when suddenly the technology became available for you to look at those creative ideas that you independently wanted to pursue?

Sadia: I had originally been fascinated by the moving image and I had always wanted to work with moving images. Part of the problem was that, certainly through the late 1970s and the 1980s when I was coming up, in order to work with moving image you really needed to have an AVID system that in those days cost around a hundred and fifty thousand pounds. It was completely beyond my means – but in the 1990s we started to see the Internet and computing starting to feed through and in the early 2000s, and I think it was 2003, there was a massive speed bump in the processing power of Apple computers. Their chip suddenly got a lot faster and it meant that you could now edit video and do post production on an Apple computer system with Final Cut Pro. Your entry point was probably around ten thousand pound mark and that was my entry point.

Evelyn: I’m thinking – you had these ideas in your head and suddenly you have the means of production – that has to be like a very exciting moment.

Sadia: It was phenomenal. I had the most incredible start to my career in moving images. The first film that I worked on premiered at the Melbourne International Film Festival in 2004. The first installation that I filmed and produced was purchased by ACMI, the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, for their permanent collection and ran on the external and internal screens at Federation Square for three months or so. They have a program that loops every half an hour. So I shot out of the blocks and I haven’t really looked back since.

Evelyn: Let’s talk about this record producer who got their hands on Final Cut Pro and started making their work in England and all of a sudden it’s on in Melbourne and it’s showed at the Melbourne International Film Festival. Talk me through the process of getting it there. How did that happen?

Sadia: Well I’ve always had a modest profile in Australia. In 1995/1996, I was part of a world music fusion group with Stephen Tayler and we were signed to Australia. The album that came out of that was called that EQUA which was ARIA nominated. I flew to Australia to do a promotional tour for a week where I did seventeen interviews a day for five and a half days.

Evelyn: Gruelling!!!

Sadia: Well, I had planned to tour Australia but when the five and a half days were up I just went straight to the airport. I thought I’ll just go home, have a little lie down and come back. And in fact, I did come back in 2004 – so it was a bit of a long lie down.

Evelyn: What you were saying is really interesting in terms of this sort of synergy between music and your art – it always feeds into music, sound and images.

Sadia: Indeed. I’d like to finish my story about my relationship with Australia. The Melbourne International Film Festival were the people who said yes. They embraced us with both arms. We had a wonderful premiere, and that led to my introduction to ACMI and then that led to my artist’s residency at Gertrude Contemporary and their international artist residency. That was where this work ‘Ghosts of Noise’ was originally workshopped in 2009.

Evelyn: So 2009 puts us in these socio-economic political sphere of the global financial crisis.

Sadia: Yes, and that’s part of what inspired this work. The work has been ten years in the making. It has material that spans 10 years from 2009 to 2019. Historically I had paid no attention to the news whatsoever. I decided at one point in my life to ignore it and I thought that if something important enough happened somebody would tell me about it.

Ghosts of Noise, by Sadia Sadia, installation image, RMIT Gallery, 2019. Photo by Mark Ashkanasy.Evelyn: Well that’s what happens, now isn’t it, except you’re being told on a feed somewhere rather than just word of mouth.

Sadia: Well, these days I think that you’re being told constantly. I think that it’s almost impossible to escape from it unless you cut yourself off and unplug completely. But in 2008 I lifted my head, and felt as that there was something going on out there, because it was starting to get very noisy.

Evelyn: That’s the point of when the noise – of the twenty-four hour news cycle – takes off really isn’t it. That’s around the time it started to be constant.

Sadia: Yes, you can actually feel the decibels of the media output heightening. It got to the point where it actually got my attention and so I started looking at news and I started looking at news feeds. Then I started looking at the information delivery complex and at the aesthetics of the information delivery complex because when I turned my attention to it, it was completely overwhelming and boy was there was a lot of it.

It was inescapable. And then of course in September 2008, we were as we now know on the verge of the complete collapse of the global financial system, five hours away in fact. I think that really brought the media outlets to such a pitch and such a frenzy that it was, even if you were intent on avoiding the news cycle completely, impossible to ignore. Once I started paying attention to it, I became fascinated by it, and then of course I couldn’t look away.

Evelyn: It is hard to look away especially when, as you show us with ‘Ghosts of Noise’, you’re being looked at aren’t you? That’s the thing with those newsreaders. They are talking constantly to you, and at you. And it can be very confronting. Where you looking across the spectrum of news sources?

Sadia: Yes. I looked across the widest possible spectrum of news sources that I had access to. I can’t mention any names, but yes, I took material from absolutely everywhere and it is something that has been a theme in other work that I’ve done is that I do try to look at the broadest possible spectrum of human experience. For me as an artist, it’s self-defeating for my purposes to restrict myself to, say, just the right wing news media, unless I was specifically trying to make an observation about that particular ethos.

Evelyn: Can you talk about how Ghosts of Noise was selected for The Model Citizen exhibition?

Sadia: Actually, I was the one who got in touch with the curators Sean Redmond and Darrin Verhagen. I had been having an email conversation with Sean that arose out of my interest in how people are emotionally affected by immersive film installations comprising sound and moving images. So I was having this conversation with Sean, I said “You know, one of the things that I’ve always wanted to do, that I’ve never actually succeeded in doing is seeing the complete installation, a proper installation for ‘Ghosts of Noise'”. And I sent him the background and a draft of what the work was about and I said ‘you know someday, (I had no idea about this exhibition) I just would really like to see this work running as it ought to’. He wrote back and he said “Darrin and I have been thinking that we might put together an exhibition called The Model Citizen, do you think you might be interested including the work in the show.

Evelyn: So it was a yes?

Sadia: Yes (laughter). So let’s just say I was delighted to accept his offer and I am thrilled with the installation.

Evelyn: So it’s a highly technical installation as well. So when you were keen for it to be somewhere, it’s interesting that a work like this doesn’t just throw itself together does it?

Sadia: I was keen for it to be installed as I had envisaged it in the fullness of my vision for the work. It also requires a not inconsiderable gallery space. We’re sitting in that space right now as everybody can see. It does require an element of technical expertise to mount it but the work itself was built in sequencing software and as I said, over a period of 10 years.

The most recent material went in during the January 2019 government shutdown in the United States. It contains material that spans that period of time and there are the technical aspects of putting together which are quite sophisticated. To go into a tiny bit more, the work on the screen behind us is actually a composite of static images which are 24 layers of news stories and 96 layers of news broadcasters signature themes, plus 256 layers of voices comprising newscasters and interviewees. The centre panel is in fact the ‘Blend’ channel which is twenty channels of male and female newsreaders, newscasters and correspondents.

The central ‘Blend’ image is in fact a non-gendered image. It comprises both men and women to create the ghost, a ‘ghost of noise’ that is ambivalent, that can be read across a whole spectrum of interpretations. To my left is the ‘Male’ channel which is six channels of feeds of male newscasters and 256 layers of voice based audio soundtrack. And to my right is the ‘Female’ channel which has six channels of layered feeds of female newscasters and 256 layers of voice based audio soundtrack of female newscasters. So the audio is running in this room through eight speakers, four stereo pairs, and the images are semi-transparent and layered one on top of the other in order to produce the generic every man, every woman and every person. To produce the ghosts or the ‘Ghosts of Noise’ which is in fact the title of the work.

Ghosts of Noise, by Sadia Sadia, installation image, RMIT Gallery, 2019. Photo by Mark Ashkanasy.Evelyn: I had a interesting comment today from one of the teachers as I was taking some school students around the exhibition; when we came to your work, she said “it’s like a waterfall, it sounds like a waterfall” and I think once you’re in here, it is. I thought that is so great because it’s what we are being exposed to. It’s almost like you’re standing at Niagara Falls, with that rush of noise. Yet her young students felt calm and happy in the space, they lay on the floor and felt comforted by the noise.

Sadia: In my mind this is the internalized noise. This is the noise that we actually live with without necessarily being conscious of it. I feel that as an artist, I don’t have the answers to the questions about what constitutes a civil society but what I can do is I can pose the questions, and certainly in this work one of the things I’m highlighting is that degree of noise that we internalize from the twenty-four hour news cycle.

I certainly felt that, by starting to watch the news, I had begun to internalize this level of noise, and I found it really troubling because it was a phenomenon in my consciousness that was almost palpable. My desire was to actually rid myself of it by performing this exorcism where I cast out these ‘ghosts of noise’. During the process of building them in the material world, my internal space became much quieter. Which is what I like.

I like my mind to be calm and be quiet and not filled with noise, so through making this work, I actually restored my sense of calm and quiet. I’m hoping that when people experience the work, they’ll recognize the sound as a noise they have internalised. That it is in fact the noise of media, and that it is in fact the noise of the 24 hour news cycle, and it is ubiquitous and it is palpable.

I’m very interested in the comment that the students were comforted by the noise, because they’ve actually grown up in this environment, so they’ve internalized it to a point where they don’t actually recognize that it exists. I think that you may be a generational divide between people who find silence comforting and people who find noise comforting.

Evelyn: Let’s now talk about other themes in ‘The Model Citizen’, such as what happens to a person’s digital legacy. Students visiting the exhibition are shocked to think that their digital footprint wouldn’t be erased when they die. They are surprised to learn that their image may live on and end up in an art gallery, like the old images of people from decades of old photos used by artist Patrick Pound in his work in the exhibition.

Sadia: I think it was (the writer and futurist) Arthur C Clarke who recommended that everybody produce hard copy of anything they wanted to last because all of these digital systems are dependent on electricity. They are dependent on power and that if the power stops, all of it stops. So another question I would raise, and once again please remember I’m the person with all the questions, not necessarily with the answers, is if your digital footprint is completely erased, if the power stops, if the grid goes down, and believe me this is not impossible, I’ve been living in Melbourne for a while now and so I see the grid going down all the time. So if the power goes, does your identity go with it? If electricity fails, do you lose your identity when you your digital footprint? Who are you without it?

Evelyn: I would immediately think of who I was before that. But that’s because I have a pre-digital life. But if you don’t have a ‘who I was before that’, if you are the age of my children for instance, and your whole world has only been about digital, then I think that is terrifying. But I remember what I was before I was able to access all of this.

I’ve always say to my children jokingly, we are only a power failure away from stupidity. If we can’t Google something, what happens? Do we have the books around? You know, this is what’s scary. As a writer I have a vast library, and I constantly get criticised for that: what do you want all those books for? Have you read them all? If you’ve read them why do you need to keep them? What’s the point of them? It’s to keep me safe, it’s to remember.

Sadia: Now that’s fascinating because I also have a large library and I am constantly asked all the same questions. I find I actually need to fight for my library. I don’t need to remind myself of what I used to be before the digital age because I make a point of living on a daily basis as if it did not exist. I am sometimes ridiculed for insisting on hard copy, taking the work that I produce and that I value and outputting it on large printers and archival formats on paper that lasts for five hundred years. But I subscribe to the philosophy, and I do believe, that there may very well come a time when power is not as freely available as it is now. It would be so easy to make all of this disappear. All you really need to do is pull the plug.

Evelyn: I’m really interested in that idea that your work is here at RMIT Gallery and you’ve recently completed your PhD also at RMIT, how does that fit into your journey? And also I guess a sense of yourself as both an artist and an ideas person? Can to talk about that?

Sadia: That’s a very broad question. I’m heavily invested in technology. Just because I say that I make a point of making sure that I have an identity outside of the digital world, doesn’t mean that I’m not completely engaged with technology, and that my work isn’t very heavily dependent on the technology that we have. I would hope that my work would continue to remain as cutting edge and as much on the leading edge of technology as it possibly can.

I embrace technology wholeheartedly. I work with every tool that’s available to me. I love it. I was a shockingly early adopter to technology, especially as a woman. I was building a website back when the rooms were completely full of boys and men. So yes, I have always been an early adopter. I love technology, but that doesn’t mean that I’m foolish or that I’m blind. I think that the philosophy of technology is something that we certainly need to take a closer look at, especially when looking at the motivation behind some of the technologies that are being developed.

I was technology that allowed me to fulfil my vision in 2003 and this was a vision that I’d been holding onto for decades. So I adore technology and I embrace it.

Evelyn: Well I guess the point that I’m interested in is the idea of an artist sort of going into the rabbit hole if you like and exploring these ideas and this philosophy and really in-depth in the doctorate. How has it, if at all, influenced yourself and your work?

(left) Sadia Sadia, with (centre) Professor David Forrest, Professor of Music Education in the School of Art at RMIT University. Opening night, The Model Citizen, RMIT Gallery, 2019. Photo by Margund Sallowsky.Sadia: There was a point I was going to make about universities because I know that universities are confronted by a great deal of criticism and a lot of the time the criticism is the only thing that they hear. I think that by and large these days we all actually live in echo chambers. What we do is we seek information and attitudes that reinforce what we have already chosen to believe. What I think is essential for an artist to do, is be conscious of the fact that as human beings we tend to veer towards echo chambers, and that it requires an effort of the will to break out of an echo chamber that you’ve created for yourself. As an artist one of the things that I wanted to do was challenge myself.

There is a saying that says ‘you don’t know what you don’t know until you know what you don’t know’ and I was always painfully aware of the fact that I didn’t know what I didn’t know. So the only way to progress, the only way to actually move forward, the only way to develop, for me, was to deliberately seek out a situation where I would be challenged by people who had other ideas, who didn’t necessarily agree with me, who had been reading literature that I was unfamiliar with, and who would force me to think about myself and my work and my place in the world in a completely different way. And that’s the benefit of universities.

That’s where universities really come into their own. It forces you to confront ideas that you may be not be comfortable with or that you may be unfamiliar with. It challenges you as an individual. I think that for all the criticism and all the failings that universities are forced to confront in the media on the daily basis, I think that the great virtue is the depth of knowledge that you can find an institution, and that is a virtue that is often almost completely overlooked.

Of course it’s been very difficult and challenging for me to move from complete liberty to working with the rules and structure of an institution but it has been an invaluable process. It forced me to see and to grow in ways that I never expected. So does that answer the question?

Evelyn: It certainly does. I think that curiosity may expose one to being unsettled and being a bit uncomfortable and also as you said, to being challenged. You have a very interesting perspective, as someone who has achieved so much in an area that you so wanted to achieve in, and who has broken through the glass ceiling, and as you said, been an early adopter of technology, and then via your doctoral study, exploring deeper other ideas, and being challenged.

Sadia: The PhD doesn’t just challenge you on an intellectual level. I mean for me there has been an element of personal growth as well. I never realized until I actually found somebody I trusted, whose notes I was prepared to take, how shattered my confidence had been by my experiences in recording studios, throughout my 20s and early 30s. And the thing that it has forced me to confront is how difficult it is, when you break somebody’s confidence, for them to reassemble it.

This is particularly true of women I hesitate to say, and I think that this is a very gendered conversation. Although it applies across the spectrum, of course, but I think that you can be unconscious of the fact that your confidence has been really badly broken and that you lost faith in some of your ideas. Actually, I’d like to take that back. I never lost faith in my ideas. But I didn’t recognize my shaken confidence until I started to see it coming out in my writing.

Evelyn: How did you keep your faith? In yourself and your work?

Sadia: It’s a very difficult question. I think that it’s a combination of a lot of factors but I think that the single most important quality in my case is my stubbornness. I refuse to give up. I slow down sometimes and I have indulged in a certain amount of escapism and hedonism, but in the end I kept going. In the end, I held on to my vision and persisted. But there are artists who persist throughout their lives whose work is never seen until after they’re dead and there are many incredibly talented people working out there today who will never be heard from and whose work will never be seen. I think that it’s a peculiar combination of skills and some of them are very much in conflict with one another.

I think I’ve had to work on a fairly intuitive level. Artists require isolation and artists need to think and artists need to be open and artists need to take in everything. On the other hand, that level of vulnerability is incompatible with going out and trying to get your work seen in the world. Trying to break through. So I think on a purely statistical basis, that if your work is good, that sooner or later it will get noticed. But I hesitate to say, unfortunately that’s not true.

I do have extended periods of total withdrawal and that is part of what allows me to go out into the world. It’s almost like I can go out into the world and I can take my meetings and hustle (as you said). I can put my work out there and say I really need to do this, I really want to see this, this is important, this matters and this is why. But for every period of time that I have when I can find the resources to do that, I need extended periods of time when I’m completely quiet, and I don’t see a soul except one or two people.

Evelyn: Thank you. It’s always interesting to hear what it takes to have a long career and I think people look at a successful career and think that there are just ‘wins’ everywhere. It takes so much persistence and so much pushing one’s self as well as the actual creativity. And let’s not forget for works such ‘Ghosts of Noise’, that take great technical skill too. This is the expertise that goes hand in hand with the thought process, with a concept and the originality. So it’s wonderful to hear this story from you, so thank you Sadia.

So what I’d like to do now is to put some questions to the audience and I would like if you could use the microphones so we can put them in the recording. So questions anyone?

Audience Member 1: Thank you for generously sharing your experience, your career development. Especially when you’re talking about the huge process of completing your PhD. I am completing my PhD at the moment so as an artist I think that’s actually parallel of exploration. Like you said there is this long area to the unknown and this notion of knowing and knowing what you don’t know. I have a question about this observation of the audience becoming very calm in front of ‘Ghosts of Noise’. I was thinking how this becomes a distraction and I was wondering if artists have their own distractions from the evident and physical distractions in front of us? What is your opinion on this?

Sadia: There are many levels of interpretation that are possible to place on the work. I sometimes run this work throughout the day in my studio in the United Kingdom because I like it. I find, to me there’s a comforting element in it as well. But at the moment I’m also suffering from tinnitus which came on very suddenly and I’ve been looking for ways to mask it. So what the sound does, is it covers the noise that’s quite literally inside my head and it makes it possible for me to think clearly. To use that as a metaphor, I think that what you’re saying is of course it’s possible. I think I prefer not to place interpretations on the work but to let people arrive at their own reading of the work themselves. That’s why generally I don’t discuss individual pieces of work in quite as much depth as I have done here. But yes of course it’s possible.

Audience Member 2: I’m fascinated that you took a conversation with your tinnitus. As a musician I have rather terrible tinnitus as well. And when I came into the room a couple of hours ago, I was captivated by it. I’m sorry if you remember a pre-internet world and so on but I often enjoy white noise, like the rain on a tin roof. It’s inspiring and it induces creativity. But you know I enjoy that background noise in order to make my own noise, if you like so, it was interesting to discuss that. I was interested in the intuitive aspect of your art. I’d like to make a comment. I like the way the digital looks very analogue. Is it because there are so many layers? Do you think that the work becomes quite analogue in a sense? The way it presents to me seeing these clusters of noise seems quite similar to old TV’s and things. Do you think that those layers morph into something else?

Sadia: I think the reason why it has an analogue quality is because the feeds are recorded from television sets and I think that the layering does give it a more analogue feel. It is interesting because it is such a heavily digital medium and yet it does have that analogue feel. I think that when we see images that are effectively distressed in this way we tend to associate those sets of images with analogue, and I think that when we see highly specified digital like 4K we associate that with ultra, super sharp, crisp, hyper-real almost cartoon-like images. I think that one of the reasons why it does feel analogue is because it does come from a television feed. And I think it would probably feel more digital if it was crisper and if the images were less distressed.

Audience Member 3: I had to use my sound meter on my phone to observe and ask myself what was this noise? And roughly my phone came out at 80 DB, which is equivalent to standing on the curb side of a busy city street, as an analogy. I didn’t find the voices uncomfortable at all. mean it’s not oppressive to my ears, I found it really comforting. Was there an aesthetic consideration to that, to that balance?

Sadia: I think that some of the considerations are to do with the environment in which the work is being shown. I think 80 dB is about right. The audio for this work can be configured in a number of different ways, depending on the space. This configuration is for four stereo pairs. It was originally designed as twelve single channels but that’s a technical feat that is almost impossible to deliver unless you have phenomenal resources at your disposal.

This sound design is very specific to this room. It can be set up in any number of different ways, and if there is more isolation between the sound sources the audio will read differently. It’s great for the space which it’s being shown. I’m just overjoyed to have this work running in this room, in this way, and I think that certainly the audio aspect of it could be pulled out and treated as an installation on its own. So was it deliberate? Yes. Is this configuration the absolute standard? And my answer to that is, it’s variable. It can be adapted for different spaces. And in different spaces it will be different. Of course you need to be conscious in public spaces of health and safety. As we were installing the work I was saying, make sure it’s just loud enough to be uncomfortable. And although, when we put the work in, I said it should be just loud enough to be uncomfortable, a number of people seem to find it curiously comforting.

Audience Member 3: Yes, that was my experience. Can I ask you one last question? Was there a moment when you were assembling the audio that it began to take on that noise quality? That all of a sudden the voices, you know, converged into something more than a series of individual voices?

Opening night, The Model Citizen, at RMIT Gallery: audiences viewing Sadia Sadia’s work Ghosts of Noise. Photo by Margund Sallowsky, 2019.Sadia: I don’t know. You’re talking about working in a very linear way, which is almost like beginning with material and seeing where it takes you. My process is exactly the opposite of that. I know what I need to hear, I can hear it, and I can see it as a mental image and hear it as an auditory hallucination. I know exactly what it needs to be and then I will work backwards from there. So my process as an artist is to try to materialise the vision that I have in my mind, rather than beginning with a set of materials and then trying to make something out of them. Sometimes I exceed my expectations and sometimes what I wind up with is a completely different piece of work than my internal vision. But it always starts as a whole. It’s always fully formed when I get it. Sometimes I wonder if I’m some kind of receiver.

Evelyn: Okay Sadia that was fascinating to hear. You talk about the creative process and being ‘a receiver’, I thought that was very interesting. And something to continue conversations about at another time perhaps. But for now I would like everyone to thank Sadia Sadia for her talk.

Sadia: Thank you.

Sadia Sadia’s work the Ghosts of Noise is exhibited as part of The Model Citizen, 8 February – 23 March 2009, RMIT Gallery, Melbourne.

Story by Evelyn Tsitas